8 Human rights due diligence

How can human rights due diligence procedures be set up?

This section explains in detail the HRDD procedures set forth in the UNGP, the OECD Guidance and other instruments. For the structure of the HRDD procedures, this tool uses the six-step approach of the OECD Guidance and the UNGP. It is important to note that neither of these two sets of guidelines takes precedence over the other.

Conducting human rights due diligence

- Embedding the responsibility to respect human rights into policies and embedding these policies into management systems and oversight bodies

-

The commitment of an organisation to responsible business conduct, including human rights, should be reflected in the policies of that organisation. Organisations are advised to develop specific policies on the most significant risks for them, building on findings from human rights risk assessments. Human rights policies should be known and available to employees and partners/ suppliers along the supply chain.

The OECD Guidance advises organisations to embed these human rights policies into management systems and oversight bodies, including the board, so that they will become part of the regular day-to-day management of the organisation. The relevant senior management and implementing departments should have communication channels to regularly share documentation on risk, decision-making processes and due diligence procedures.

How organisations can practically embed the human rights functions in their organisation is explained in more detail in the paragraph on human rights due diligence within the organisation.

- Identifying and assessing actual and potential human rights impacts

-

Identifying and assessing actual and potential adverse human rights impacts is a crucial step in the HRDD process according to the OECD Guidance and the UNGP.

As a first step, the OECD Guidance advises large organisations, including MNEs, to carry out a broad scoping exercise to identify all areas of the organisation - across its operations and relationships, including in its supply chains - where human rights risks are most likely to occur. Sources for this scoping can include reports from governments, international organisations, civil society organisations, workers’ representatives and trade unions, national human rights institutions or media. Where gaps in information exist, the organisation should consult stakeholders and/ or human rights experts. The most significant human rights risks should be prioritised as the starting point for a more in-depth assessment.

For small organisations, for instance SMEs, a scoping exercise may not be necessary before moving to the stage of identifying and prioritising specific impacts.

After an organisation has identified and prioritised the most significant human rights risks, it should continue with a more in-depth study on the prioritised risk areas. This includes consultation and engagement with impacted and/or potentially impacted individuals and/or communities to gather information on adverse impacts and risks. In the context of human rights, it is important to pay special attention to risks for individuals belonging to groups or populations that may have a heightened risk of vulnerability or marginalisation, and to differentiate risks that may be faced by women and men. Organisations should consult potentially impacted individuals and/or communities both prior to and during projects or activities that may affect them.

When the risks have been identified, the organisation will continue with an assessment of the level of its involvement with the actual or potential adverse human rights impacts, in order to determine the appropriate responses. The level of involvement and the organisation’s relationship to the human rights impact will be explained in the section on human rights due diligence in the supply chain.

Drawing from this assessment, organisations should prioritise, where necessary, the most significant human rights risks and impacts to be addressed, based on severity and likelihood.

The UNGP indicate a range of approaches that may be appropriate for organisations to assess human rights impacts. Examples of such approaches include “stand-alone” human rights impact assessments, which are assessments that focus exclusively on human rights, and “integrated assessments”, which integrate human rights into environmental, social and health impact assessments. The section below focuses on stand-alone human rights impact assessments for organisations.

- Human rights impact assessments

-

A human rights impact assessment is an instrument for examining policies, corporate activities, programs and projects to identify and measure their effects on human rights. Human rights impact assessments are based on the normative framework of binding international human rights law.

A selection of guidance on how to conduct a human rights impacts assessment is presented in this section. This is not an exhaustive list. Examples of actual human rights impact assessments are listed and described in tool 10.

United Nations

According to the UNGP, more specifically Guiding Principle 18, organisations should do the following when assessing their human rights impacts:

Draw on internal and/or independent human rights expertise; Undertake meaningful consultation with potentially affected rights-holders and other relevant parties; Be gender-sensitive and pay particular attention to any human rights impacts on individuals belonging to groups that may be at heightened risk of vulnerability or marginalization; Assess impacts from the perspective of risk to people rather than risk to business; Repeat risk and impact identification and assessment at regular intervals.

The UN Global Compact Guide to Human Rights Impact Assessment and Management (2011) provides guidance on how to assess and manage the human rights risks and impacts of an organisation through a process divided into seven stages:

- Preparation: define the scope of the human rights impact assessment;

- Identification: identify and clarify the human rights context

- Stakeholder engagement: two-way interaction between the organisation and its key stakeholders;

- Assessment of human rights impacts and consequences

- Mitigation: develop appropriate action plans;

- Management: integrate human rights within the management system;

- Evaluation: including monitoring assessments, external and internal reporting and evaluating the effectiveness of the management system.

UNICEF and the Danish Institute for Human Rights have published a tool, Children’s Rights in Impact Assessments (2013), that guides organisations in assessing their performance in respecting children’s rights. It can also be used to integrate children’s rights considerations into ongoing assessments of overall human rights impacts. It offers a number of criteria that organisations can use both to review potential or actual impacts on children’s rights and to identify actions for improvement. The criteria offered in the tool cover the ten Children’s Rights and Business Principles. The impact assessment criteria for each of the ten principles encompass the following areas: policy, due diligence and remedy.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group has published the IFC Performance standards on environmental and social sustainability (2012). The report details the standards that IFC clients have to meet throughout the life of an investment by IFC. It provides guidance on how to identify risks and impacts, and is designed to help avoid, mitigate, and manage risks and impacts as a way of doing business in a sustainable way, including through stakeholder engagement and disclosure obligations.

Non-governmental organisations

The community-based human rights impact assessment: the Getting it Rights tool (2011) was developed by Oxfam and the International Federation for Human Rights(FIDH) in partnership with Rights & Democracy. The tool provides a methodology for conducting a community-based, participatory process to analyse the human rights impacts of private foreign investments. It enables communities and the organisations that support them to identify human rights impacts, propose responses, and engage government and corporate actors to take action to respect human rights. The tool focuses on local communities on their role as experts and advocates.

The CSR IMPACT Project Practitioners handbook on corporate impact assessment and management (2014) contains a short strategy guide for owners, executives and managers of organisations on corporate impact assessment and management. It entails a detailed explanation of corporate impact assessment and management from a managerial perspective, and a proposed methodology to embed this into day-to-day business. The research was conducted by several universities and financed by the European Commission.

Conducting an effective human rights impact assessment (2013), published by BSR, gives guidelines for and examples of human rights impact assessments that align with the UNGP. It gives step-by-step guidance on four levels of impact assessments: corporate, country, site, and product.

Initiatives from other countries

The Danish Institute for Human Rights has developed a human rights impact assessment Guidance and Toolbox (2016) to facilitate impact assessments of organisations using a human rights-based approach consistent with the UNGP. The toolbox divides the impact assessment into the following phases:

- Planning and scoping;

- Data collection and baseline development;

- Impact analysis;

- Impact mitigation and management;

- Reporting and evaluation.

The toolbox guides users in detail through these different phases and gives detailed guidance on stakeholder engagement throughout this process.

- Integrating and acting upon the findings: ceasing, preventing and mitigating adverse impacts

-

According to the OECD Guidance and the UNGP, organisations should stop activities that are causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts. They should also develop and implement plans to prevent and mitigate potential adverse human rights impacts. In doing so, organisations are advised to consult and engage with impacted and potentially impacted stakeholders and rights-holders to develop appropriate actions and implement the prevention and mitigation plans.

In case of actual or potential adverse human rights impacts that are associated with partners of the organisation along the supply chain, appropriate responses include:

- Continuation of the relationship throughout the course of risk mitigation efforts;

- Temporary suspension of the relationship while pursuing ongoing risk mitigation;

- Disengagement from the relationship if:

- attempts at mitigation have failed;

- the organisation deems mitigation not feasible;

- the severity of the adverse impact demands immediate action.

Possibilities for appropriate action are discussed in detail in this tool, in the section on human rights due diligence in the supply chain.

- Tracking implementation and results

-

The OECD Guidance and the UNGP identify performance tracking (including drawing lessons from this for the organisation) as an important step in the HRDD process. Tracking is necessary for an organisation to know if its human rights policies are being implemented optimally, to know whether it has responded effectively to identified human rights impacts, and to drive continuous improvement. For many organisations, tracking effectiveness will also include monitoring the performance of suppliers, customers and other partners.

Tracking should be integrated into relevant internal reporting processes. Organisations might employ tools that they already use in relation to other issues. This could include performance contracts and reviews, as well as surveys and audits.

The OECD Guidance advises organisations to track the implementation and effectiveness of their due diligence activities, meaning the measures they take to identify, prevent and mitigate impacts, as well as support remedy for these where appropriate. This includes such measures taken with partners in the supply chain.

Organisations can carry out periodic internal or third party reviews or audits of the outcomes achieved. Consultations with impacted or potentially impacted rights-holders are also important for tracking performance. Organisations that belong to a multi-stakeholder initiative are advised to encourage or request periodic reviews.

The lessons learned from tracking should be used to improve HRDD processes in the future.

The UNGP Reporting Framework states that a system for tracking an organisation’s responses to human rights impacts may simply review how it has responded to the (potential) impact, and to what extent these responses prevented the impact. However, if a significant human rights impact has occurred, the organisation is advised to additionally undertake a root cause analysis to identify how and why the human rights impact occurred. This kind of process can be important if the business is to prevent or mitigate the continuation or recurrence of the impact.

- Communicate how impacts are addressed

-

It is crucial for an organisation to communicate publicly on how human rights impacts are being identified and addressed. Organisations should provide a measure of transparency and accountability to individuals or groups who may be impacted and to other relevant stakeholders, including investors.

The OECD Guidance advises organisations to report all relevant information about the due diligence process externally. This information should be easily accessible and appropriate - for instance, on the website of the organisation, at the premises of the organisation, and in local languages. If some of the information published is specifically relevant to impacted or potentially impacted rights-holders, this should be communicated with them in a timely, culturally sensitive and accessible manner.

According to UNGP Principle 21, communications should in all instances:

- Be of a form and frequency that reflect an organisation’s human rights impacts and that are accessible to its intended audiences;

- Provide information that is sufficient to evaluate the adequacy of an organisation’s response to the particular human rights impact involved;

- Not pose risks to affected stakeholders, personnel, or legitimate requirements of commercial confidentiality.

It is important that organisations report publicly on risks and risk management along the supply chain, because this facilitates the engagement of other organisations in the supply chain. Detailed reporting enables the entire supply chain to share in the responsibility of addressing risks.

- Provide for or cooperate in remedy

-

Both the OECD Guidance and the UNGP expect organisations that have caused or contributed to actual adverse human rights impacts to address such impacts by providing for or cooperating in their remediation.

The OECD Guidance sets out practical actions that organisations can take when they have caused or contributed to adverse human rights impacts:

- Seek to restore the affected person(s) to the situation they would have been in if the adverse impact had not occurred (where possible) and enable remediation that is proportionate to the significance and scale of the adverse impact;

- Comply with the law and seek out international guidelines on remediation. Examples of remedies include: apologies, restitution or rehabilitation, financial or non-financial compensation, punitive sanctions or taking measures to prevent future adverse impacts;

- Consult and engage with impacted rights-holders and their representatives in determining the remedy;

- Evaluate complainants’ level of satisfaction with the process provided and its outcome(s).

Organisations can, when appropriate, provide for or cooperate with legitimate judicial or non-judicial remediation mechanisms. Some situations, in particular where crimes are alleged, require cooperation with judicial mechanisms.

The UNGP give guidance on remediation that is similar to the OECD Guidance. Additionally, the UNGP describe criteria to ensure the effectiveness of grievance mechanisms. Through an operational-level grievance mechanism, affected stakeholders can raise concerns about any impact they believe an organisation has had on them, in order to seek remedy. The mechanism should help to identify problems before they escalate and provide solutions that include remedy. Tool 9 discusses grievance mechanisms and remedy in detail.

Stakeholder engagement in the human rights due diligence process

Throughout the entire HRDD process, it is key to understand the perspective of potentially affected individuals and groups.

Where possible and appropriate to the organisation’s size or human rights risk profile, this should involve direct consultation with those who may be affected by the organisation’s products, services or relationships. For a small organisation with limited impact, a simple means for people to give feedback may be sufficient, such as an accessible e-mail address or phone number.

It is very important that organisations engage stakeholders in a meaningful way. Poor engagement can increase the risks of negative human rights impacts on stakeholders. In practice, many human rights impacts can be linked back to challenges related to stakeholder engagement.

The UNGP note the importance of consulting with affected stakeholders at several key moments:

- When identifying and assessing actual and potential human rights impacts;

- When tracking and reporting on the efforts of the organisation to prevent and manage those impacts;

- When designing effective grievance mechanisms and remediation processes.

Affected stakeholders may include:

- Staff (employees and contract workers) and communities directly affected by the organisation’s operations;

- More physically remote stakeholders affected through by the organisation’s operations in the supply chain;

- Customers or end-users of a particular product or service.

Civil society – including NGOs, grassroots community organisations, researchers and academics – may be trusted representatives of vulnerable groups. Moreover, civil society organisations can be important players in providing independent oversight of stakeholder engagement and in holding organisations accountable for adverse human rights impacts. They can put the public spotlight on abusive practices and bring organisations to the negotiating table.

Human rights due diligence within an organisation

The UNGP expect organisations to embed the responsibility to respect human rights within their internal structures – at every level of the organisation and across all functions and departments.

Organisations need to allocate the necessary internal capacity to manage adverse human rights risks effectively. For an SME with limited human rights risks, it will likely be a task that can be allocated to an existing member of staff. For larger organisations, or those faced with a high probability of a particular human rights impact, it will require a more systematized approach. This may involve structured collaboration across departments, clear internal reporting requirements, regular interactions with external experts, and/ or collective action with others.

It is important to note that there is no single, correct approach to embedding the responsibility to respect human rights within internal structures. The most effective approaches will take full account of the particular context of the organisation, including the most immediate challenges it faces in fulfilling its responsibility to respect human rights.

Below, this tool describes examples and best practices regarding how organisations can allocate responsibility for identifying, preventing and mitigating actual and potential adverse human rights impacts, as well as account for how they address them.

- UN Global Compact Good Practice Note on organizing the human rights function within a company

-

The UN Global Compact Good Practice Note on organizing the human rights function within a company (2014) examines different models for how responsibility for human rights can be assigned internally within the organisation. The Note offers lessons and insights from a range of organisations’ experiences.

As noted above, the question of how best to organize human rights functions within an organisation is especially relevant for medium and large organisations. In small organisations, many of the relevant functions will be consolidated under the responsibility of a single manager, so the challenges of cross-functional coordination may be less significant.

The Good Practice Note describes four possible models:

- Cross-functional working groups, which bring together different departments within an organisation in a collective platform to address and manage human rights risks. These working groups typically hold responsibility for coordinating human rights activities horizontally across the departments of the organisation, and vertically down to country-level operations.

- Hosting a ‘guide dog’ function within one of the existing departments. Because one department often lacks the power to compel implementation by others, the focus here is typically on awareness raising, information sharing, support and guidance to help other departments to fulfil the overall responsibility to respect human rights.

- Legal and/or compliance-driven ‘guard dog’ models, which place greater emphasis on oversight, compliance and accountability for implementation of human rights policies and processes.

- Separate responsibilities allocated across different departments, through which various departments, based on their respective areas of expertise, assume responsibility for different aspects of the responsibility to respect human rights.

The Note stresses that organisations do not have to fit within one of these models. The Note also clarifies that these models do not necessarily represent preferred options. Organisations will typically combine features of the abovementioned models to fit their way of working.

- Blueprint for embedding human rights in key company functions

-

The European Business Network for Corporate Social Responsibility has developed a Blueprint for embedding human rights in key company functions (2016). The blueprint presents six key common elements that organisations should consider, regardless of their corporate culture, their business activities, or the positioning of different functions within their structure.

These elements are:

- Cross-functional leadership: ensure effective management of human rights issues;

- Share responsibility for outcomes;

- Incentivise: set appropriate performance goals for all staff and align incentives to reflect management commitments;

- Provide operational guidance and training for all staff at all levels throughout the company;

- Foster two-way communication between management and operational staff;

- Review and analyse the company’s performance on human rights, and share and integrate lessons internally.

Human rights due diligence in the supply chain

The OECD Guidance and the UNGP expect organisations to implement HRDD in their supply chain. Organisations should manage their supply chains responsibly, meaning that they should ensure that their chains of suppliers and/or subsidiaries respect human rights.

The UNGP state that organisations may be involved with adverse human rights impacts either through their own activities or as a result of their business relationships. Organisations are expected not only to avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts, but also to address “human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.”

These business relationships are understood to include relationships with partners of an organisation, entities in its value chain, and any other non-state or state entity directly linked to an organisation’s operations, products or services.

Besides the OECD Guidance and the UNGP, other tools give detailed guidance on supply chain due diligence. A selection of these tools are listed below:

- UN Global Compact

-

The UN Global Compact has published several guidelines for organisations on sustainable supply chains. The guide Supply chain sustainability (2015) outlines practical steps that businesses can take to achieve supply chain sustainability. The recommended steps summarized are based on the UN Global Compact Management Model (2010). The three essential principles for successful supply chain sustainability management are governance, transparency and engagement.

A structured process to prioritize supply chain human rights risks (2015) centres on integrating respect for human rights into supply chain management. The Note focuses on the process that businesses should follow to identify their priority supply chain human rights risks in a way that aligns with the UNGP.

- Non-governmental organisations

-

The Shift workshop report Respecting human rights through global supply chains (2012) discusses challenges and gives practical examples of how organisations can respect human rights throughout their supply chains. It restates the UNGP due diligence steps and touches upon their application in sensitive, high-risk areas.

From audit to innovation: advancing human rights in global supply chains (2013) is a report published by Shift that discusses a new generation of social compliance programs for supply chains. It recognizes the limitations of conventional social compliance auditing and explores innovative models used by leading organizations.

CREM and SOMO have published a report, Responsible Supply Chain Management (2011), on potential success factors and challenges for addressing prevailing human rights issues, as well as other CSR issues, in the supply chains of EU-based organisations. The study provides insight into the reasons that responsible supply chain management has not yet proven to be a solution for some of the CSR issues encountered in supply chains.

SOMO’s study on Multinationals and conflict (2014) gives an overview of the existing principles and guidelines for organisations operating in conflict-affected areas, so that affected communities and workers can use them in their dealings with organisations in case of business-related human rights violations.

- Other

-

The British Institute of International and Comparative Law and Norton Rose Fulbright published a report and analysis that guides organisations in due diligence processes in supply chains. Making sense of managing human rights issues in supply chains (2018) discusses the challenges of due diligence in the supply chain and gives practical advice.

Human rights due diligence applied to the supply chain

- Identifying and assessing human rights impacts in the supply chain

-

Adverse human rights impacts can occur at any level of a supply chain, from the first tier of direct or strategic suppliers, all the way down via multiple layers of sub-suppliers and sub-contractors to those providing the raw material inputs. To fulfil their responsibilities, organisations need to understand human rights risks at all levels of their supply chain.

Mapping the supply chain is often not a straightforward exercise, as modern supply chains are vast, complex and dynamic. The most common challenge in conducting due diligence in the supply chain is a lack of transparency.

Internally, departments that have direct interaction with entities in the supply chain - for instance, the purchasing or procurement departments - can assist in the mapping exercise. Externally, the organisation needs the cooperation of suppliers themselves to identify subsequent tiers in the supply chain.

For organisations with vast supply chains, it may be unreasonable in terms of time and resources to assess the human rights impacts of each supplier. In such cases, the UNGP state that companies should identify general areas “where the risk of adverse human rights impacts is most significant, whether due to certain suppliers’ or clients’ operating context, the particular operations, products or services involved, or other relevant considerations, and prioritize these for human rights due diligence.” According to the UNGP, prioritization should be solely based onthe severity of the adverse human rights impact on stakeholders, independently of the nature of the link between the organisation and the impact.

- Ceasing or preventing a relationship with adverse impacts in the supply chain

-

Where an organisation contributes or may contribute to an adverse human rights impact, it should take the necessary steps to cease or prevent its contribution and use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impact.

Where an organisation has not contributed to an adverse human rights impact, but that impact is nevertheless directly linked to its operations, products or services by its business relationship with another entity, the situation is more complex. To determine the appropriate action, the following factors are important to consider: the leverage the organisation has over the concerned entity, how crucial the relationship is to the organisation, the severity of the adverse human rights impact, and whether terminating the relationship with the entity itself would have adverse human rights consequences.

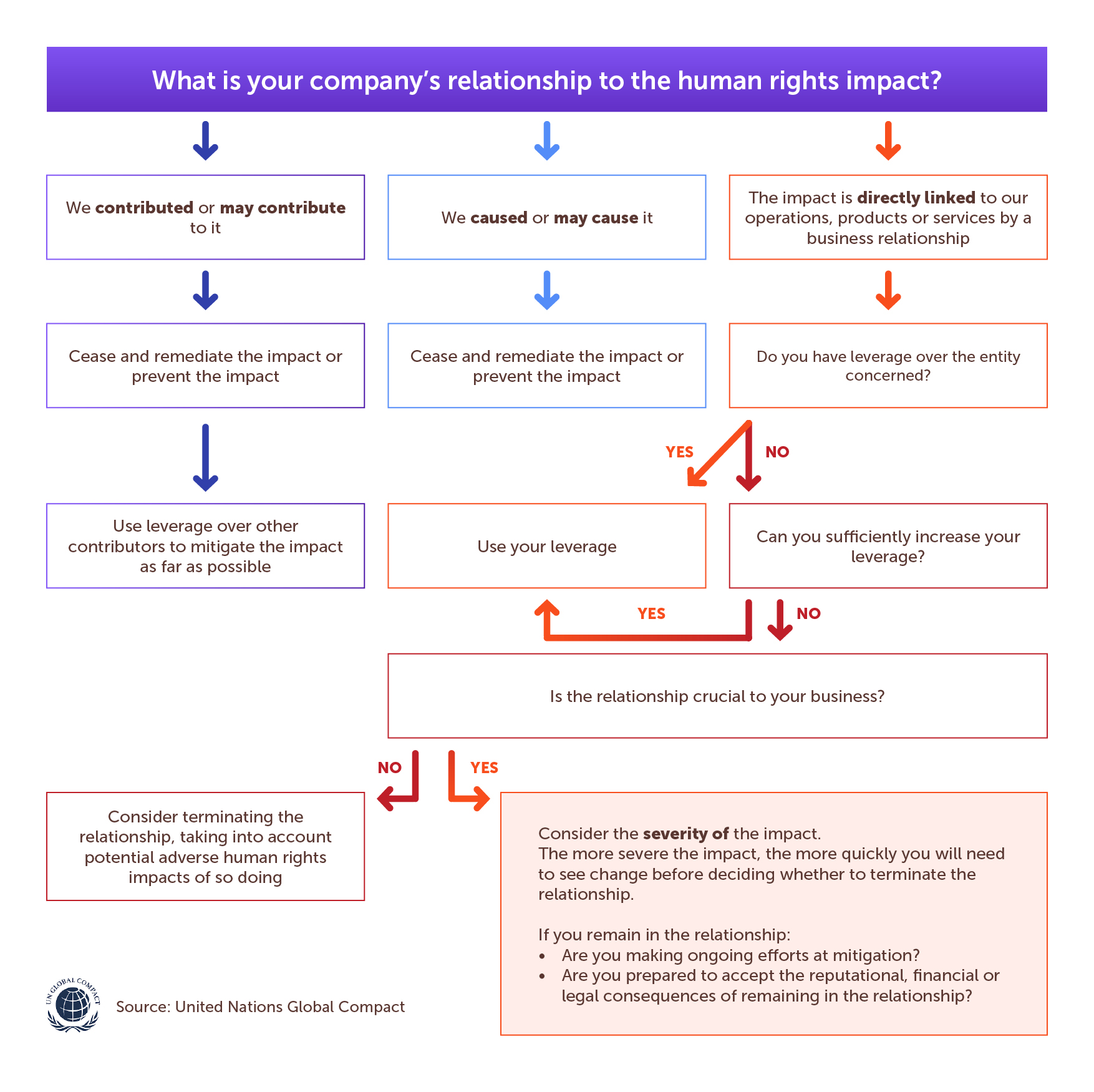

This image illustrates the possible relationships between an organisation and a human rights impact, as well as the associated appropriate actions. The actions are discussed in more detail below the image.

Leverage is considered to exist where the organisation is able to effect change in the wrongful practices of an entity that causes harm. An organisation’s leverage stems from the unique relationship it has with a particular entity, including the commercial or reputational importance of the relationship.

Organisations typically have the strongest leverage at the point before entering into a relationship with an entity. It is recommended to include human rights provisions in a contract or an accompanying code of conduct to prevent an adverse human rights impact in the supply chain. Contractual provisions have more impact on suppliers when complemented by other due diligence components - for instance, compliance monitoring, embedding human rights policies and action plans into the suppliers’ operations, and human rights training.

The UNGP state that organisations should exercise their leverage over the entities in the supply chain to mitigate or cease the adverse impact. If an organisation lacks leverage, there may be ways to increase it - for instance, by offering incentives to the related entity. Where an organisation lacks leverage and is unable to increase this, it should consider ending the relationship, taking into account the potential adverse human rights impacts of doing so.

If a relationship is crucial to an organisation, ending it will raise challenges. A relationship could be crucial if it provides a product or service that is essential to an organisation and no reasonable alternative source exists. The severity of the adverse human rights impact must also be considered in a decision on whether to end a relationship. The UNGP state that for as long as an abuse continues and an organisation remains in the relationship, it should be able to demonstrate its own ongoing efforts to mitigate the impact and be prepared to accept any consequences – reputational, financial or legal – of the continuing connection.

There is limited HRDD practice beyond the first tier, where no contractual relationship exists between the organisation and the entity that caused or contributed to the adverse human rights impact. Leverage beyond the first tier is usually exercised either indirectly through the first-tier entity – for, instance through codes of conduct that require a first-tier entity to impose similar standards on the next tier - or through collective engagement with peers or other stakeholders.

- Tracking implementation and results in the supply chain

-

Audits are traditionally used to track the implementation and results of due diligence practices in the supply chain. However, recent research has found that traditional auditing processes are insufficient to detect human rights impacts. Audits can serve as a tool for identifying current shortfalls in standards, but they are only a snapshot in time.

Some organisations have shifted their emphasis away from relying on compliance auditing towards more collaborative approaches, such as working with suppliers to assess gaps, build capacity, and incentivize sustainable improvements. Other organisations use audits that are specifically focused on human rights to monitor compliance with their human rights provisions and codes of conduct.

To monitor compliance in the supply chain and obtain information and insights on the local environment, it can be useful for an organisation to work with local experts (temporarily) on the ground.

- Communicating how impacts are addressed in the supply chain

-

Managing supply chains responsibly can be very challenging. It is therefore even more important for organisations to combat lack of transparency in supply chains. Communicating on due diligence efforts in the supply chain enables organisations to convey internally and externally the seriousness with which they are addressing challenging issues.

The increased public pressure on organisations to be transparent and manage their supply chains responsibly, coupled with the difficulties for organisations with many entities in their supply chains to provide transparency, spurred on several initiatives to assist organisations with public reporting. For instance, the Global Reporting Initiative aims to support organisations in their reporting processes. The International Trade Centre developed the Sustainability Map to increase transparency by connecting businesses and producers.

- Remediation in the supply chain

-

As explained above, potential human rights impacts can be one or more steps removed from the organisation. This makes effective grievance mechanisms at the level of the supplier particularly important in helping to ensure that potential impacts can be identified and addressed in a timely fashion.

However, the use of operational-level human rights grievance mechanisms in the supply chain, especially beyond the first tier, appears to be limited in practice. Where available, this is often an organisation’s grievance mechanism that is available to those whose rights are affected by its supply chain. In other cases, organisations expect their suppliers to put grievance mechanisms in place.